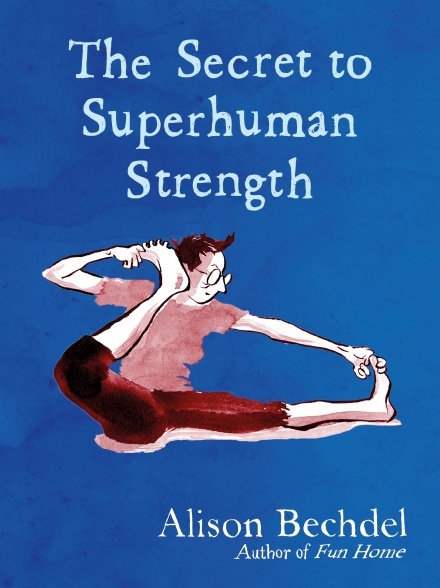

Q&A with Alison Bechdel: The Secret to Superhuman Strength

Alison Bechdel is a queer and feminist icon.

She rose to fame after creating the iconic comic strip Dykes To Watch Out For, which ran for 25 years, and writing the graphic novels Fun Home and Are You My Mother?. She is the recipient of a McArthur ‘Genius’ Award, and the musical adaptation of Fun Home won a Tony Award for Best Musical. She lives in Vermont with her partner Holly.

In The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Alison uses exercise as lens through which to explore her own mental and physical health – from her childhood through to the current day. Like all of her work, it’s funny, intensely personal, moving and profound. As part of our summer sport campaign, we were lucky enough to talk to Alison about her new book.

It felt like a lot of the book was about your relationship to your work, and about moving from refusing help from others to accepting it (at least from your partners). That feels like a major shift, and a freeing one. What kind of possibilities does that open up for the future?

I hope it opens up the possibility of letting other people in even more deeply. The day will come, I expect, when I really need physical assistance and I would like to be able to accept it graciously instead of resisting it, thereby making the whole process more difficult than it needs to be.

I found myself going from crying at a page about death to laughing at a joke on the next page. And, of course, Fun Home’s subtitle is ‘A Family Tragicomedy’. When you work, are you consciously mixing serious and humorous topics, or have these things always naturally coincided for you?

It’s a pretty organic mix for me—I did grow up in a funeral home, after all. Joking about serious things was just something my family did.

At what point did the book turn from a ‘fun’ project about exercise into a chronologically told life story, and when did Margaret Fuller come into the mix?

The book was initially going to have a calendar structure—one chapter per month of the year. January would have a lot of skiing in it, for example. But it just wasn’t working, and at some point I realized I needed to literally begin at the beginning, with my birth in 1960. Margaret Fuller came into the mix when I was researching The Whole Earth Catalog—a book that had made a big impression on me as a kid.

The architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller was a big inspiration behind The Whole Earth Catalog project, and then I learned that Bucky had in turn been inspired by his great aunt Margaret! I’d read a great biography of her a few years earlier, and had fallen in love with her. So this link between the transcendentalists and the hippies was exciting to me—there was a clear intellectual lineage there, of which I was a part.

Your work often interacts with politics, even if it’s in ‘subtle’ ways (e.g. newspapers/TV in the background). What’s the thinking behind that, other than to orient the reader in time?

I find the political world a bit baffling, and I’m always trying to work out the way it connects with our individual lives. The older I get, the more I can see that the two realms operate according to the same laws. Actually, it’s one law—narcissism. But what I’m trying to show in this book is that true self-interest necessarily entails other-interest. Instead of our barbaric survival-of-the-fittest mentality, we need to see each other, understand that we all depend on each other, and then work for the collective good. I don’t actually spell all that out in such a didactic fashion, but I hope that’s the message that comes through.

The end of the book takes us up to the present day, with you and Holly switching off from the outside world and slowing down together. How has the pandemic impacted your attitude to work and other priorities in life?

My year-plus quarantine demonstrated something I already knew: that I love staying at home. I’ve had to travel a fair amount in recent years, and it has really been a disruptive and creativity-sapping force. I can’t even express how much I loved just being at home month after month, not even going out for dinner but just staying put on my little patch of land. I felt very bad for people trapped in their city apartments, though—I’m not sure how I would have handled that. Holly and I spent our spare time making paths in our woods, then walking them in endless loops.

It came through how hard it was to be catapulted to fame and to do huge amounts of press around very personal books. Have you found that fans/strangers can cross boundaries in the way they relate to you (in part because your work is quite unboundaried)? How have you handled this?

I haven’t found that to be a problem, really. People in general seem to be fairly respectful. But perhaps that’s due in part to the fact that I’ve retreated so much over the years. I’ve kind of drawn in my head like a turtle. A turtle that has to go out and do periodic rounds of publicity.

Guen’s character was featured briefly but made a huge impression. A lot of your work seems to be around memorialising people. What is it that motivates you to do that, and how do you go about getting it ‘right’?

I tried to be careful not to just use Guen to make a point or fill out my narrative, but to really honour who she was. She was a remarkable person who died quite suddenly and much too young. But she was also my partner Holly’s other girlfriend, which made the loss complicated. I guess it’s just a natural extension of grief for me to try and figure it out in my work—a cerebral approach perhaps, but also one that pushes me to really examine my own emotions.